Since the irreverent Duchamp’s Roue de bicyclette (1913), the research of contemporary has focused on questioning the basis of the artistic concept.

The issues involved are above all the meaning of the masterpiece, its definition, its destination, the institutional spaces that legitimize it, the market logic to which it is subjected.

By painting the moustache to Gioconda, Marcel Duchamp interrogated his audience about the drama of the “icon”, just as, by signing his models, Manzoni posed the problem of the artist’s authorship. It has the power to define the value of any object that, automatically, becomes a “work of art”.

When contemporary research embraces the realm of decoration, the artist can hardly ignore these questions. The sumptuous world of jewellery is linked to the notions of wealth, luxury, seduction, fashion, social membership. Artists like Karin Seufert, Philip Sajet, Karl Fritsch, play on the overthrow of preconceived canons, on the ambiguity of their works and the disorientation of the viewer. All of them have been guests of Preziosa, where they exhibited works that highlight the internal contradictions of the rich world of ornament.

Karin Seufert, N.T. Necklace, 299, 2008, PVC, artificial leather, alumina, elastic (black), courtesy of the artist. Preziosa 2013

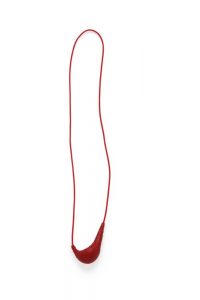

Karin Seufert, Nikelace, necklace, 319, 2011, PVC, elastic, paper, courtesy of the artist. Preziosa 2013

Karin Seufert analyzes the implicit statement of those who wear a precious jewel. Human desire is linked to the appropriation of symbols that declare the belonging to an elite group. Sports brands, such as Puma, Nike or Adidas, reflect in a more commercial view the same intention that motivates the purchase of a Cartier panther. The historic sacredness of an onyx cameo, outcome of engraving skills, is lost in the incongruous use of PVC, an easy-to-work industrial material.

Karl Fritsch, Ring, 2008, silver, oxidised, glass stones, courtesy of the artist. Preziosa 2009

Karl Fritsch, Ring, 2006, white gold, rubies, sapphires, diamonds, courtesy of the artist. Preziosa 2009

Another “visual contradiction”, as a metaphor for the destructive human ambition, is produced by Karl Fritsch‘s jewellery.

Like Babel towers, acts of ostentatious pride, his rings defy the laws of physics, stacking real or fake gemstones, which seem to be about to collapse under their own weight. Diamonds and rubies are mixed with plastic and glass pearls, tricking the beholder. The notion of beauty and preciousness are so carried to the extreme, to the point when they become unpleasant and almost grotesque.

That desecrating attitude is not so far from the famous Déjeuner en fourrure by Meret Oppenheim, who in 1936 covered a little cup, its saucer and its spoon, symbols of the bourgeois salons of Paris, with luxurious fur, creating a bewildering reaction in the viewer.

Philip Sajet, Black diamonds, broken blood and pearls, necklace, 2010, glass, niello on silver, pearls, gold, courtesy of the artist. Preziosa 2013

Even Philip Sajet plays on the duality of what we see and what it really is: his jewels are sometimes worthless copies of the famous ones and seem to console the impossible desire to possess them. Like Fritsch, Sajet combines pearls and corals with synthetic or glass stones, making us think on the price of human exploitation for the gemstone mining. When we buy expensive jewelry we become accomplices, and his rough and pointed stones like daggers lay bare the violence of a conniving society, greedy for what is valuable.

But what is the “value” when it comes to contemporary jewellery?

The glass stones by Sajet and Fritsch, as the Seufert’s PVC, take on worth in the issues their creations open. Just like the Oppenheim’s fur cup, they light up a sad reality that exploits for its enrichment the weaknesses and contradictions of the human being. The traditional rules on which the jewel-object is based, from the stone setting to its highly execution, undergo a reversal, a disruption. These artists rely on their own need to go beyond their certainties and beliefs about jewellery, to probe an insidious field such as the embellishment of one’s person and the desire for possession.

Meret Oppehneim, Object (Déjeuner en fourrure), 1936